1 what is “data science for the liberal arts?”

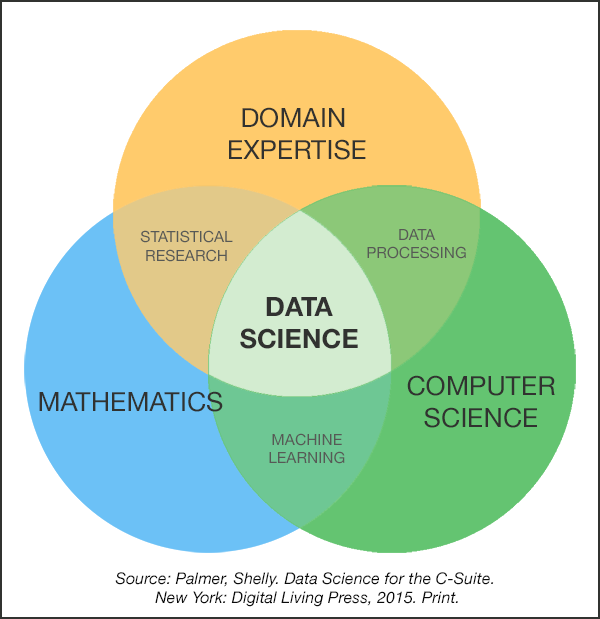

Hochster, in Hicks and Irizarry (2018), describes two broad types of data scientists: Type A (Analysis) data scientists, whose skills are like those of an applied statistician, and Type B (Building) data scientists, whose skills lie in problem solving or coding, using the skills of the computer scientist. This view arguably omits a critical component of the field, as data science is driven not just by statistics and computer science, but also by “domain expertise:”

The iconic Venn diagram model of data science, as shown above, suggests that there are not two but three focal areas in the field, one of which begins not with math or computer science, but with “domain expertise.” Data science for the liberal arts is a ‘Type C’ approach, where ‘C’ might refer to a concentration of concern in the arts, humanities, social and/or natural sciences. For the Type C data scientist, coding is in the service of applied problems and concerns.

Type C data science does not merely integrate ‘domain expertise’ with statistics and computing, it places content squarely at the center. We can appreciate the compelling logic and power of statistics as well as the elegance of well-written code, but for our purposes these are means to an end. Programming and statistics are tools in the service of social and scientific problems and cultural concerns. Type C data science aims for work which is not merely cool, efficient, or elegant, but responsible and meaningful.

At the risk of oversimplifying:

Type A data scientists focus on Analysis and questions about ‘how?’

Type B data scientists focus on Building and questions of ‘what?’

Type C data scientists focus on Consideration and questions of ‘why?’, ‘who?’, ‘what for?’, and ‘at what (social) cost?’

1.1 the incompleteness of the data science Venn diagram

Data visualizations are starting points which can provide insights, typically highlighting big truths or effects by obscuring other, presumably smaller ones. The Venn diagram model of data science is no exception: As with other graphs, figures, and maps, it allows us to see by showing only part of the picture. What does it omit? That is, beyond mathematics, computing, and domain expertise, what other skills contribute to the success of the data scientist?

1.1.1 additional domains

For the liberal arts data scientist, we can note at least three additional important domains, that is, communication, collaboration, and citizenship.

Communication, including writing and the design and display of quantitative data, is central to data science because results are inconsequential unless they are recognized, understood, and built upon. Facets of communication include oral presentations, written texts and good data visualizations.

Collaboration is important because problems in data science are sufficiently complex so that any single individual will typically have expertise in some, but not all, facets of the area. Collaboration, even more than statistical and technical sophistication, is arguably the most distinctive feature of contemporary scholarship in the natural and social sciences as well as in the private sector (Isaacson 2014).

Citizenship is important because we are humans living in a social world; it includes serving the public good, overcoming the digital divide, furthering social justice, increasing public health, diminishing human suffering, and making the world a more beautiful place. The Type C data scientist is aware of the fact that the world and workforce are undergoing massive change: This puts the classic liberal arts focus of “learning how to learn” (as opposed to memorization) at center stage. Finally, the Type C data scientist is sensitive to the creepiness of living increasingly in a measured, observed world. These real-world goals should be informed by ethical concerns including a respect for the privacy and autonomy of our fellow humans.

1.1.2 an additional dimension

Cutting across these various facets (statistics, computing, domain expertise, collaboration, communication, and citizenship), a second dimension can be articulated. No one of us can excel in all of these domains, rather, we might aim towards a hierarchy of goals ranging from literacy (can comprehend) through proficiency (can communicate and contribute) to fluency (can practice) to leadership (can create new solutions or methods).

That is, we can think of a continuum of ability, including knowledge, skills, interests, and goals. That continuum ranges from the data consumer to the data citizen to the data science contributor. A Type C data science includes this dimension of ‘depth’ as well.

1.2 the importance of data science for society

Communication, collaboration, and citizenship are each associated with the concept of trust. Trust is an important social good because it is associated with both individual well being (Poulin and Haase 2015) and the stability of democratic institutions (Sullivan and Transue 1999). But interpersonal and institutional trust, including trust in science, have declined in recent years (Deane 2024). The decline in trust in science has been exacerbated by the so-called reproducibility (or replication) crisis, in which many scientific results initially characterized as “statistically significant” have been found not to hold up under scrutiny, that is, aren’t reproducible. The reasons for the reproducibility crisis are many and contentious, but there is substantial consensus that one path towards better science involves the public sharing of methods and data. A second path towards better and more trustworthy science involves the use of larger datasets: With large datasets, effects are more stable and “statistical significance” is rarely a concern. Other indices, such as measures of accuracy and effect size are typically of primary interest. Data science, with its tools for reproducible analysis and its use of big data sets, can make science more trustworthy and improve the quality of our lives.

1.2.1 intelligence, artificial intelligence (AI), and careers

It is difficult to predict the consequences of advances in AI for career selection. Some areas are likely to be impacted by AI more than others, but because AI is still in its infancy, we can only speculate. But one way to approach this question is to begin by considering what constitutes “intelligence.” According to Robert J. Sternberg (2018), intelligence can be thought of as having three components. One of these is Analytical Intelligence, which includes things like planning, reasoning, acquiring knowledge, and problem solving. A second is Creative Intelligence, which includes both the ability to deal with novel situations effectively, and the ability to “automatize” or efficiently execute familiar tasks. The third is Practical or Contextual Intelligence, which includes the ability to adapt to new environments.

AI engines or agents (or simply AIs) are, for now at least, effective at only some of these. They are better than humans at knowledge acquisition, logical reasoning and some kinds of problem solving. All of these are parts of Analytical Intelligence. They are also better than us at one part of Sternberg’s Creative Intelligence: They excel at many types of automatized routines.

Beyond this, they struggle. My desktop AI (Microsoft Copilot 365 Version 19.2508.31121.0) tells me that the strengths of AI, understood in the context of Sternberg’s theory, make it ideal for things like “Data Analysis, Financial modeling, Diagnostics, Scheduling and logistics, and Repetitive administrative tasks.” The first and last of these are core parts of data science, but not the whole of it. AI struggles (again, according to Copilot), with “Leadership and strategic decision-making, Counseling, therapy, and social work, Cross-cultural negotiation, [and] Artistic innovation requiring deep emotional resonance.” Careers that are likely to grow include creative professions (design, storytelling), human-centered roles (coaching, diplomacy), and also hybrid roles, that is, “Professionals who use AI tools to enhance their work (e.g., data-informed decision-makers).”

All of this should be taken with a grain of salt. Today’s AI capabilities are quite limited compared to what they will be a year from now, and the AI that you and I might use on our desktops is, in all likelihood, a simple version of what is already available to large-scale users.

Oliver is an embodied AI described as a “helperbot” in the recent Broadway musical Maybe Happy Ending. We can imagine that a helperbot like Oliver could be built on a model that synthesized millions of interactions between people in asymmetrical roles, such as butlers and their employers, secretaries and bosses, and assistants and supervisors. In the musical, Oliver appears to have been an ideal servant, one who anticipated his owner’s needs consistently, promptly and sensitively.

I won’t spoil it for you, but Maybe Happy Ending can be seen as portraying the challenges AI agents face, and how Artificial Intelligence is different from human intelligence. In Sternberg’s (2018) terms, Oliver struggles not just with the question of how to adapt to a new environment, but also how to choose an environment altogether. How will it react when it encounters problems for which it has simply no frame of reference?

1.2.2 the challenge of TMI

The challenges of data science are many, but perhaps the most fundamental is the problem of (literally) TMI. When we compare traditional statistics with modern data science, we realize that the former is typically concerned with making inferences from datasets that are too small, while the latter is concerned with making sense of data that is or are too big (D. Donoho 2017). The basic challenge of working in data science is the challenge of “too much information,” or TMI.

The challenge of TMI is not new, or restricted to data science. In the 19th Century, Wilhelm Wundt argued that attention was the distinguishing act of the human mind (Blumenthal 1975). That is, in attending to (or focusing on) something, we must overlook everything else, consequently, selection is the essence of human perception (Erdelyi 1974). Selection is important not just in psychology, but in the arts as well, for editing, or choosing what not to write or show, is at the core of the creation of works including novels and film (Ondaatje and Murch 2002).

Although the problem of TMI is not new, today it exists at a much greater scale, for there is simply more information around us. Indeed, over the last 20 years, the amount of digital information in the world has increased roughly 200-fold.2

Like perception in psychology and editing in the arts, data science is concerned with extracting meaning from information. Because the amount of information around us has mushroomed and its nature has become more important, our need to extract meaning has become more ubiquitous and more urgent. For these reasons, data science is a foundational discipline in 21st century inquiry.

References

According to Wikipedia, the Zettabyte (ZB) Era began in 2012, when the amount of digital information in the world first exceeded 1 ZB (or 1021 bytes). In 2025, it is estimated that the world will house 175 ZBs of digital data (Reinsel, Gantz, and Rydning 2025), hence a 175X increase in in 13 years. My estimate of a 200X increase in 20 years is a conservative extrapolation from these numbers. Incidentally, one ZB = 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 bytes, which could be stored on roughly 250 billion DVDs, or 500 million 2 TB hard drives.↩︎